| Back to Eric's Home Page | Up to Site Map | $Date: 2001/02/28 05:59:28 $ |

This paper describes a mode of the Tengwar of Feanor adapted for the writing of the artificial language Esperanto.

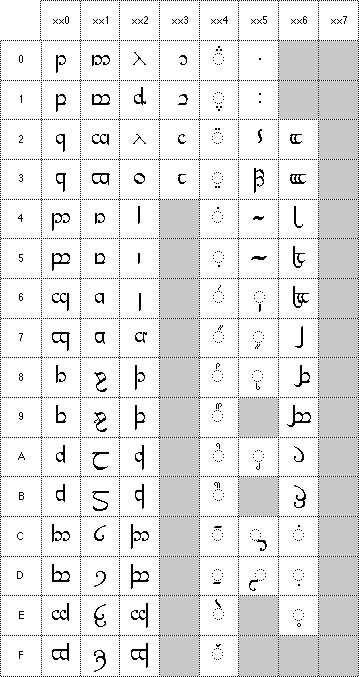

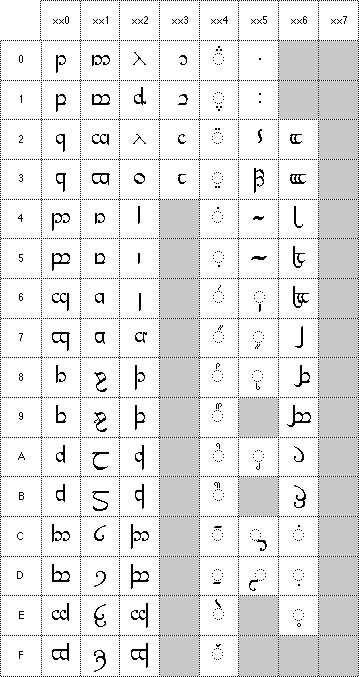

The original Tengwar chart is in the appendices to The Return of the King (volume III of The Lord of the Rings (the chart is in Appendix E, page 494 of the Ballantine pb edition). References to the Tengwar in this paper can be chased to this chart:

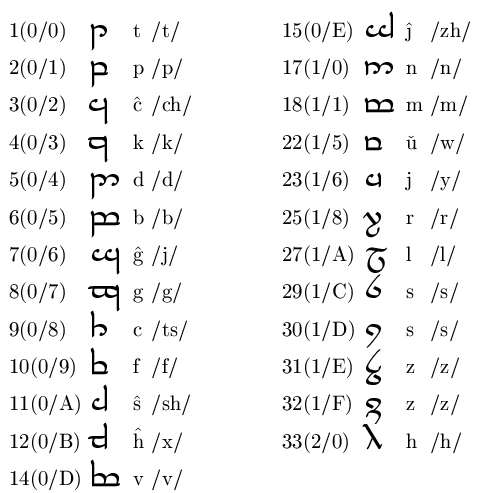

The chart is copied from Michael Everson's Unicode/ISO 10646-2 proposal for the Tengwar. References are this given as given as n(x/y), where n is Tolkien's number, x is the table column number and y the row number. Where Tolkien describes a tehta that appears in the Everson table but is unnumbered, I reference it simply as (x/y).

In studying what follows, it is particularly important to remember that in any given mode the Tengwar consonants form a phonetic grid in which alterations in form correspond to alterations in sound in a predictable way. Before continuing, you should probably reread (or at least re-skim) Tolkien's discussion of the Feanorian letters, pages 495-500 following the chart.

Here is a summary of the relationships: There are 24 primary Tengwar letters. The letters are organized into four series or "Témar". Each series is used to represent sounds created by different parts of the mouth. Series I and II are almost always used for dental and labial sounds. Series III is generally used for either palatal or velar sounds and series IV for either velar or labiovelar sounds, depending on the phonology of the language represented. These four series were further broken down into six grades or "Tyeller". Each grade is used to represent sounds created by different ways that air flows through the mouth and nose. Grade 1 and 2 were used for voiceless and voiced plosives. Grade 3 and 4 were used for voiceless and voiced fricatives (including, in modern terminology, affricates). Grade 5 was used for nasals. Grade 6 was used for semi-vowel consonants. Each Tengwar letter was assigned a phonetic value determined by its position in this grid. People speaking different languages will often re-define this grid, so only a few of the letters have a fixed phonetic value.

Vowels may be represented either by "tehtar" (diacriticals or accent marks written above a preceding or following vowel) or by dedicated letters ("full-writing"). Some other diacriticals and letter modifications ccan be used to indicate dipthongization, following s, and lengthening.

The basic facts we need to begin constructing a Tengwar mode for any given language are (a) a phoneme inventory, and (b) whether its basic syllables are "closed" (consonent-ended, like English and Tolkien's Westron) or "open" (vowel-ended, like Italian or Tolkien's Quenya).

Esperanto has 34 phonemes. They are as follows:

The phonotactics of Esperanto are neither regular nor well described. The main issue for our purposes is whether closed or open syllables predominate. On the one hand, almost every basic word has a vowel ending (indicating its grammatical type). On the other hand, the (common) objective inflection adds an 'n' suffix, and Esperanto (reflecting the Slavic languages its inventor was familiar with) is even richer in complex consonant clusters than English or Westron.

With a few exceptions, the consonant inventory of Esperanto is quite similar to that of English. The exceptions are /ts/ and /x/. This strongly suggests using a mode as similar to Tolkien's existing modes for English as possible:

1(0/0) = /t/ 2(0/1) = /p/ 3(0/2) = /ch/ 4(0/3) = /k/

5(0/4) = /d/ 6(0/5) = /b/ 7(0/6) = /j/ 8(0/7) = /g/

10(0/9) = /f/ 11(0/A) = /sh/ 12(0/B) = /x/

14(0/D) = /v/ 15(0/E) = /zh/

17(1/0) = /n/ 18(1/1) = /m/

25(1/8) = /r/ 22(1/5) = /w/ 23(1/6) = /y/

27(1/A) = /l/

29(1/C) = /s/ 30(1/D) = /s/ 31(1/E) = /z/ 32(1/F) = /z/

33(2/0) = /h/

We use 25(1/8) rather than the more obvious 21(1/4) because Esperanto /r/ is meant to be pronounced trilled; this makes it easier to distinguish the /r/ from the /l/, especially for speakers of Asian languages.

This gives us full-writing tengwar for every Esperanto consonant except /ts/. We could write that using /t/ 1(0/0) combined with the "right silme" sign for following-s (5/C), but it would also be useful to have a full-written version. So we should slip /ts/ into one of the gaps. The obvious position is 9(0/8), which at grade I of series 3 should be a unvoiced dental affricate (IPA theta). /ts/ is not at all a bad fit here.

We'll tackle the full-writing option first. We need a minimum of five signs, for /a/, /e/, /i/, /o/ and /u/. All of these occur in the Sindarin inscription on the West-Gate of Moria in Volume I, though not all are shown in Appendix E. In the `Mode of Beleriand', then, the vowel letters are:

We need additional signs for the dipthongs. Tolkien says that the Elves used two overhead dots (3/4) for following-y; this will handle /ai/, /ei/, /oi/, and /ui/. He also writes of the u-curl (4/A in this mode) being used above a full-writing vowel to signify following w.

Now for the tehtar. For /a/, /e/, /i/, /o/ and /u/ we can use the same tehtar used in Westron and Tolkien's mode for English (as used in the title-page inscription of LotR):

How to represent the dipthongs in tehtar? We cannot superimpose them, as there are adjacent vowels in Esperanto: "praulo" (ancestor) and "boato" (boat) are examples. Therefore we must write dipthongs as the full letter for the initial sound with a following-y or /u/ tehta above it.

We have left until last the vexing question of whether Esperanto tehtar should be written Sindarin- or Westron like (tehtar over following consonant) or Quenya-like (tehtar over preceding consonant). Inspecting words in the Esperanto corpus, it appears that `open' syllables with final vowels predominate. Thus in the 1.1 version of this mode I settled on the Quenya-like convention.

However, Erich Rickheit observes: "Esperanto is an inflected and agglutinative language; one needs to be interested in morphemes, rather than words. Most of the most common morphemes are closed; especially, the most common grammatical affixes (-et-, -ig-, -igh-, -ec-, -em-), and the commonest verb inflections (-as, -is, -os) are closed. Also, treating final syllables as open would mean that changing an inflection (say, from nominative to accusative) would change a glyph not otherwise part of the inflection, which is a bit of a dissonance."

He continues: "The other useful side effect of going to the closed mode is that the glides /y/ and /w/ become the glyph, with the vowel 'hanging on' as a tehtar, rather than being a tehtar when used as glide and a glyph when used as a consonant; this is more consistent with the Esperanto use of the Latin alphabet."

This is persuasive. I'm therefore now recommending the Sindarin style.

I have not been able to find any specification of Esperanto's punctuation rules, but it appears from texts that Esperanto employs modern European punctuation. It would be nice to have at least signs for period, comma, exclamation point, question mark, colon, semicolon, parentheses, and quote marks.

Half of these are attested in the corpus of Tengwar texts:

.

Parentheses would look perfectly reasonable in a tengwar context. Indeed, the visual enclosure of text in parentheses to set off auxiliary remarks would appeal to the Eldar fondness for making the relationships between geometric forms in their orthography meaningful.

Colon, semicolon, and quotes, however, pose a problem. They do not occur in the corpus. Colon and semicolon probably have to be mapped into the pusta "pause" sign. English quotes look rather too much like floating tehta, but French-style guillemets might do.

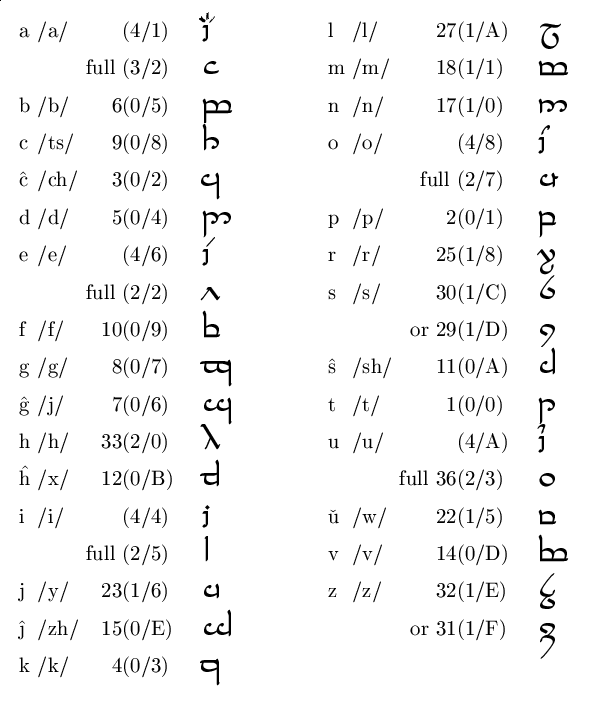

Here are all the signs and tehtar in the full mode, collected for reference:

Consonants:

1(0/0) = /t/ 2(0/1) = /p/ 3(0/2) = /ch/ 4(0/3) = /k/

5(0/4) = /d/ 6(0/5) = /b/ 7(0/6) = /j/ 8(0/7) = /g/

9(0/8) = /ts/ 10(0/9) = /f/ 11(0/A) = /sh/ 12(0/B) = /x/

14(0/D) = /v/ 15(0/E) = /zh/

17(1/0) = /n/ 18(1/1) = /m/

25(1/8) = /r/ 22(1/5) = /w/ 23(1/6) = /y/

27(1/A) = /l/

29(1/C) = /s/ 30(1/D) = /s/ 31(1/E) = /z/ 32(1/F) = /z/

33(2/0) = /h/

Full-written vowels:

(3/2) = /a/ 35(2/2) = /e/ (2/5) = /i/ 23(2/7) = /o/ 36(2/3) = /u/

Vowel tehtar:

(4/1) = /a/ (4/6) = /e/ (4/4) = /i/ (4/8) = /o/ (4/A) = /u/

Combining signs:

following-s = (5/C, 5/D) following-y = (3/4)

Punctuation:

comma or pause = (5/0) period = (5/1)

exclamation mark = (5/2) question mark = (5/3)

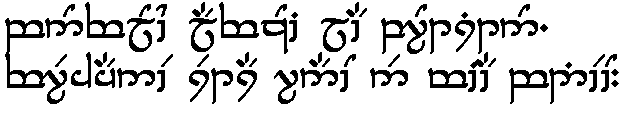

Erich Rickheit supplied these samples.

From an episode of Red Dwarf in which Rimmer utterly fails to insult his crewmates in Esperanto: "Please call the hall porter, there appears to be a frog in my bidet".

And here are Rickheit's mode tables. First, by Esperanto alphabet order:

Then by Tengwar order:

Because this source was written by a knowledgeable critic of Esperanto, I found it was up front about phonological complexities that proponents of the language tend to gloss over.

Dan Smith's Tengwar information page. Includes useful discussions of punctuation and modifier symbols.

Version 1.1, April 16 2000: Initial version.

Version 1.2, April 18 2000: Incorporated minor corrections by Geoff Eddy.

Version 1.3, September 30 2000: Incorporated JBR's corrections. /ts/ moves to 9(0/8). Note presence of vowel pairs.

Version 1.4, February 27 2001: Fixed bugs pointed out by Erich Rickheit and Douglas Brebner. I got /e/ and /o/ in the Mode of Beleriand wrong :-(. Esperanto /r/ is trilled.

Version 1.5, February 1 2016: Note that intitial /ts/ is spelled 'c' in Italian. Fix a link.

| Back to Eric's Home Page | Up to Site Map | $Date: 2001/02/28 05:59:28 $ |